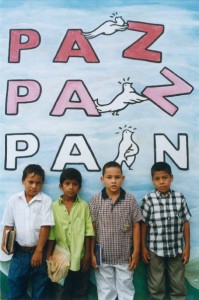

Preface: Steve Salisbury is in a special position to analyze and make recommendations for the peace talks between Colombia’s government of President Juan Manuel Santos and largest guerrilla group, the Marxist-Leninist predominantly campesino Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The peace negotiations—aimed at ending Latin America’s longest-running armed conflict of about 52 years that has resulted in up to approximately 220,000 dead and 6 million displaced people, according to some estimates—were formally initiated in Havana, Cuba, in November 2012 after an inauguration ceremony in Oslo, Norway, a month earlier and secret preliminary talks in Havana for months before that. Long based in Colombia, Salisbury, fluent in Spanish, has a background in media and private consulting, living in and covering Latin America since the early 1980s and meeting with Colombian news-makers across the political, economic, social, and armed-conflict spectrums.

Before the naming of Bernard Aronson as US Special Presidential Envoy to the Colombian peace process in February 2015, Salisbury was already carrying out since April 2013 as a “Good Samaritan” private citizen what could be seen as a de facto role of an unofficial “emissary” or “intermediary” and continues his efforts deeply following the peace process to this day. To be clear, Salisbury doesn’t work for, nor represent, the US government, isn’t part of the actual peace negotiations, and doesn’t negotiate. But it could be said that, in a way, Salisbury was a private-citizen “precursor” to Ambassador Aronson.

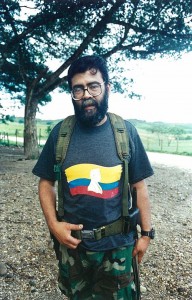

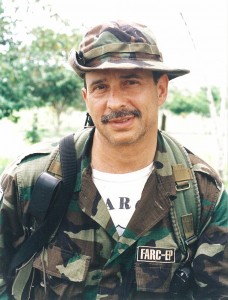

Salisbury has met in private multiple times with the FARC leadership in Havana, passing along its messages to US senior officials in Washington DC and the US embassy in Bogota, and reviewing publicly declared US official positions to FARC leaders as well as asking the FARC leadership questions on the mind of US officials or others. Salisbury had first met the FARC’s top leaders in a journalistic capacity in the year 2000 during the ill-fated peace talks under Colombian then-President Andres Pastrana, who allowed a Switzerland-sized “Distension Zone” to the FARC for over three years where those talks took place, but which was retaken by government troops when the talks collapsed in February 2002.

Since 1997, the FARC has been officially designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) by the US State Department, which the FARC rejects. Until the presidential designation of US Special Envoy Aronson, US officials had been barred from meeting with or communicating directly or indirectly with the FARC since US diplomat Phillip Chicola met officially in December 1998 in Costa Rica with the FARC’s senior-ranking “Raul Reyes” (who was killed a decade later in a controversial Colombian military cross-border airstrike about a kilometer or so inside Ecuador). That US communication with the FARC ended abruptly after the killing of three American Indian-rights activists in 1999 was imputed to a FARC unit which accused them of being spies—“an unfortunate misunderstanding and tragic accident,” according to the FARC. But what has always been permitted is if unsolicited FARC communication happens to come before the eyes of US officials, explain US officials. And that is where Salisbury came in about three years ago.

While President Obama designated Ambassador Aronson following a request by President Santos, Salisbury’s analysis beforehand on such an option was apparently taken into account by US policymakers, according to a well-placed source. Besides being taken into account by US officials and the FARC leadership, Salisbury’s observations have been kept in mind by top international peace advisers to Pres. Santos, Colombian senior military officers (active-duty or retired), respective members of the political opposition as well as of Santos’ political coalition, Colombian Congresspersons, think-tank and humanitarian executives, and victims of the conflict, among others.

Salisbury continues to provide his reports and assessments to US officials and others following the peace process. To provide greater understanding for the public discussion on Colombia, the forecast herewith is an updated, expanded version by Salisbury of one of his reports provided to US senior officials and others, with editing for purposes of anonymity in some places.