The FARC sees the situation of “Simon Trinidad” and those of at least two or three other FARC members extradited to the US and serving prison sentences there as necessary to resolve for an eventual overall peace accord, as well as to resolve the judicial situations of FARC members in Colombian jails or under indictment.

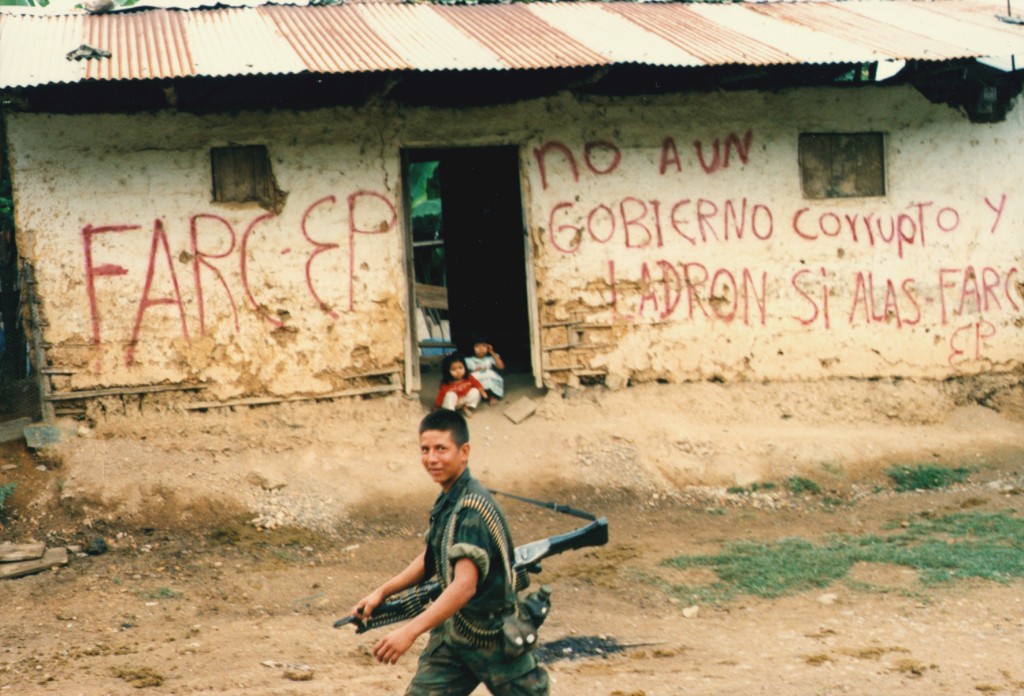

“Simon Trinidad” was arrested in Ecuador in January 2004, when the FARC says he was trying to promote peace, though which US and Colombian authorities saw as “Simon” allegedly trying to help negotiate a swap of FARC members in Colombian jails for three US citizens or others held captive by the FARC. “Simon” was deported shortly his arrest to Colombia and was extradited to the United States reportedly on Dec 31, 2004, and is serving a 60-year sentence in a US federal prison in Colorado on a conviction of an association of kidnapping charge of three US Department of Defense subcontractors whose surveillance plane crashed hundreds of kilometers away from where “Simon” was. Multiple other charges against “Simon” on drug-trafficking ended in mistrial or absolution. FARC leaders have called the conviction a miscarriage of justice, saying that “Simon” has never been in its combat/military operational command and was a kind of political spokesperson. When I visited the FARC “Distension Zone” several times during the ill-fated peace talks under then-President Andres Pastrana, I met with “Simon Trinidad” and saw him as a spokesperson or with a role on political themes and peace-process facilitation.

Ironically apparently tracking with the FARC contention on “Simon,” a Western former diplomat who when in the diplomatic corps had closely followed “Simon’s” case from the time of his arrest in Ecuador in 2004 told me, preferring to remain anonymous, that an ambitious US assistant district attorney was the driving force for the extradition of “Simon Trinidad” (already in a Colombian jail) and that the prosecutor was supposedly trying to burnish his own credentials and make a big name for himself for personal, career or political aspirations, when there was a questionable basis for the extradition and that it has caused all sorts of unnecessary complications. The former diplomat, a law-and-order hardliner who said that while “Simon” is no saint and deserved to be serving jail time in Colombia for other cases, he shouldn’t have been extradited to the United States.

“It makes me want to vomit,” the former diplomat said of what he viewed as the US assistant district attorney grandstanding. The former diplomat said, in his view, that since the prosecutor couldn’t find anyone from Al Queda and that because the prosecutor supposedly may have felt a need “to check the box” of nailing a terrorist to help climb the career ladder, he went after “Simon.” The prosecutor sees that the conviction of “Simon Trinidad” by a US jury vindicated the extradition and that justice was served. However, the former diplomat wondered if any jury not very knowledgeable of Colombia and of the FARC could fathom all the intricacies of a case like “Simon’s,” particularly in an emotionally charged atmosphere of the “war on terror.”

The FARC has always called for “Simon” to be released from US prison and sent to Havana to be part of its negotiating team. The US rejects this. Possible options that observers have raised may be for “Simon” to be remanded either straight to Colombian penitentiary custody, or to the penitentiary custody of a third country which has legal treaties with both the United State and Colombia for such a move as a kind of “half-way” stop for an eventual remanding of “Simon” to Colombia, for his sentence to be continued. However, United States international judicial treaty conditions evidently require that time of sentence and other sentence circumstances must track to a certain level with the US sentence, if a prisoner is to be remanded to another country.

The FARC thinks that a US presidential pardon or commutation of sentence could be a convenient solution. While only President Obama knows if he would eventually grant or not a pardon or commutation of sentence to “Simon,” with a Colombian overall peace accord in mind, it doesn’t appear to be on the horizon. US Presidential Special Envoy Bernard Aronson has publicly said that “Simon” was convicted of a very serious crime and has a sentence to serve. Moreover, how would Pres. Obama’s possible consideration of a pardon or commutation of sentence be affected, if at all, by a You Tube video posted months earlier of “Simon” saying several years ago that the Nobel peace prize awarded to Pres. Obama should be for the “Pax Romana”?

The FARC sees “Simon” as being a revolutionary’s revolutionary, “a man of iron” and of profound revolutionary integrity. “Simon” is a symbol for the FARC “struggle.” Having studied at Harvard University, “Simon” could be of great help in the peace process,” the FARC’s “Ivan Marquez” told me.

How to resolve the “Simon” issue? Without a presidential pardon or commutation of sentence, it would have to be via the established procedures of the US federal judicial system, through a convicted person’s right to appeals or requests for reduction of sentence, parole, probation, mitigation of prison living conditions, or other judicial considerations.

The US attorney general perhaps could have the district attorney make a petition to the court for a revision of sentence, and if granted, “Simon” could be maybe released on time served or have his case remanded to Colombia or another country, with the adjusted sentence qualifying within parameters for such a remanding. But appeals and petitions could be rejected, and if so, “Simon” would have to continue serving his sentence in a US prison. What would this mean for the peace talks? It’s a good question with no answer now.

Questions for US officials to contemplate are: If the United States releases convicted felons or suspends extradition requests just because of a peace process per se, could this weaken the US judicial system and undermine its deterrent of sentencing and of reach, in the eyes of foreign armed groups or others who harm or may harm US citizens? (A question that Colombia is similarly facing in its own peace process, as noted above.) Or would it serve a greater good in supposedly enhancing US national security by helping to bring peace, in this case, to Colombia?